The An ka taa Bambara/Dioula Dictionary

This dictionary is a work in progress.

It is conceptualized as user-friendly "pocket" dictionary -- small in size, but rich in information for students and learners of Manding since it fully marks tone and includes information about morphology, variation between Jula and Bambara, examples etc.

It is a project of Coleman Donaldson and Antoine Fenayon.

Here is its recommended citation:

Donaldson, Coleman, and Antoine Fenayon. 2021. Manding (Bambara/Jula) - English - French Dictionary. An ka taa. https://www.dictionary.ankataa.com.

On this Page

What is Manding?

From a linguistic perspective, Manding is a language-dialect continuum spoken across a massive area stretching west to east from Senegal to Burkina Faso and north to south from the Sahelian north of Mali to the forests of Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire. Traditionally, it is divided into four major named varieties: Bamanan (or Bambara), Maninka, Jula (also written Dioula and Dyula) and Mandinka. The first three, in particular, are often held to be mutually intelligible by native speakers. They are all Eastern Manding varieties characterized by a 7-vowel system. Mandinka, on the other hand, is a Western variety which has a 5-vowel system and a number of other features that make it more difficult to consider mutually intelligible in many contexts.

How to Use This Dictionary

Bambara vs Jula

Bambara is considered the “main” form of the dictionary given both that it is the Manding variety that most outsiders wish to learn and that it is a prestige variety for many Jula speakers. In most cases the words and forms are the same in both varieties. In the case of them being divergent, Jula forms are listed both as headwords that refer back to the “main” Bambara entry and as variants under a Bambara headword.

Synonyms, Variants, Main Entries

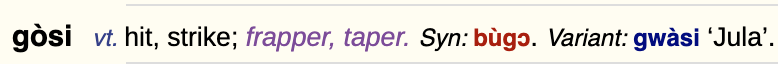

Synonyms are two different words that can usually be considered to be interchangeable. For example, bùgɔ and gòsi are two words that both mean ‘hit’. In such cases, both entries are marked by “Syn:”

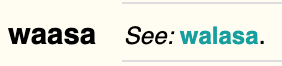

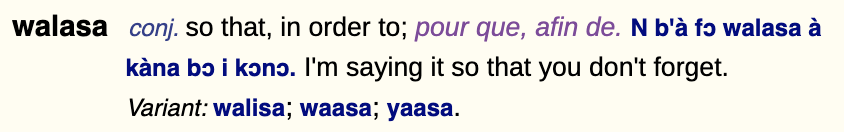

We use the term variants when a single word has two different forms. In such cases, one form is considered the main entry of the dictionary. The variant entries are generally shorter and include a link to the main entry preceded by “See:” while the main entry lists the variants following the word “Variant:”

Spelling conventions

Most large Western languages have institutional histories that have created dictionaries that most speakers defer to as offering canonical spelling regardless of actual pronunciation. If a learner needs to look a word up, but is unsure of spelling, they simply ask a speaker or search the internet with their best educated guesses.

In the case of many African languages such as Manding, where there is not a widely known established written spelling, a learner relies heavily on what one hears when looking up a word. As such, this dictionary lists a number of important variable forms/spellings that may be helpful when one is trying to look up a word as they hear it,

It is not practical, however, to include every possible pronunciation of a word since Bambara and Jula have a range of local dialects and idiosyncrasies just like English, French, Arabic etc. As such, we have adopted a few conventions to reduce the number of minor entries in the dictionary.

|

Variation |

Example |

Comment |

|

Labiovelars |

gɛ̀lɛn ~ gwɛ̀lɛn ~ gbɛ̀lɛn ‘hard’ |

By convention we note Bambara as <g> and Jula as <gw>. |

|

Word medial liquid variation |

wùlu ~ wùru ‘dog’ |

Except in a few special cases, we generally ignore the fact that Jula occasionally has <r> in place of <l> |

|

Low front vowel variation |

ɲɛ̀ ~ ɲà ‘to be good’ |

In general, we note Bambara as having <ɛ> and Jula as having <a> |

|

Intervocalic velars |

taga ~ taa ~ taka |

In general, we consider the full form (that is, with a velar consonant) as the main entry. |

Derived forms

In this dictionary, we frequently list derived forms. This means that if you look up a word, you can easily view and jump to related entries that come from the same “root”. These are listed at the end of the entry:

Sub-entries

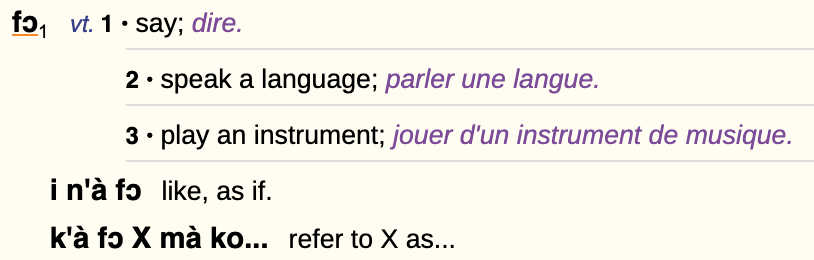

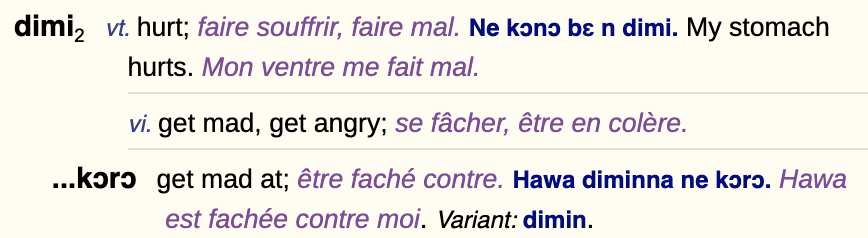

Many entries list sub-entries. In some cases, we use this for special lexicalized usages such as these that one sees at the end of the entry for fɔ:

In other cases, the sub-entries are preceded by a dot-dot-dot. This typically is used for signaling how to properly use a particular verb by way of a postposition. Dimi, for instance, uses the postposition kɔrɔ to express the idea of ‘get mad at someone’:

Alphabet

Bambara and Jula are spoken across Mali, Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire. Despite the varieties being mutually intelligible as varieties of Manding and akin to American and British English, they have slightly different national spelling conventions for Latin-based orthography that remain rarely used by most speakers of the language.

Increasingly, Manding is written using the N’ko script that was invented to write and standardize the language in 1949 by the peasant intellectual Sulemaana Kantè, but it is not yet incorporated into this dictionary project.

Below is a table of the practical Latin-based spelling system that we use this in dictionary followed by their N’ko script equivalents.

Consonants

|

Consonants |

||||

|

Latin |

N’ko |

English approximation |

Example |

Gloss |

|

b |

ߓ |

bad |

bón |

‘house’ |

|

c |

ߗ |

Chad |

cɛ̌ |

‘man’ |

|

d |

ߘ |

dog |

dɔ̀lɔ́ |

‘alcohol’ |

|

f |

ߝ |

film |

fɔ́lɔ |

‘first’ |

|

g |

- |

good |

gàribú |

‘Quranic student seeking alms’ |

|

gw |

ߜ |

*A labio-velar double occlusive—in essence, an English /g/ and /b/ at the same time, but also pronounced and written in this dictionary as “gw” |

gwǒ |

‘bad’ |

|

h |

ߤ |

hello |

hákili |

‘idea’ |

|

j |

ߖ |

jump |

jàn |

‘long’ |

|

k |

ߞ |

call |

kélen |

‘one’ |

|

l |

ߟ |

lamp |

lòkó |

‘plantain’ |

|

m |

ߡ |

might |

mɔ̀gɔ́ |

‘person’ |

|

n |

ߣ |

never |

náani |

‘four |

|

ɲ |

ߢ |

*Palatal nasal—like enseñar in Spanish |

ɲì |

‘good’ |

|

ŋ |

- |

king |

ŋɔ̀mí |

‘fritter’ |

|

p |

ߔ |

power |

pán |

‘jump’ |

|

r |

ߙ / ߚ |

*a tapped /r/ like pero in Spanish |

báara |

‘work’ |

|

s |

ߛ |

soup |

sàyá |

‘death’ |

|

t |

ߕ |

tomato |

tìlé |

‘sun’ |

|

w |

ߥ |

west |

wári |

‘money’ |

|

y |

ߦ |

yogurt |

yɛ́lɛ |

‘laugh’ |

|

z |

- |

zebra |

zùwɛ́n |

‘June’ |

Vowels

|

Vowels |

||||

|

Latin |

N’ko |

English approximation |

Example |

Gloss |

|

a |

ߊ |

wasp |

bàbá |

‘dad’ |

|

e |

ߋ |

*like manger in French |

bèsé |

‘machette’ |

|

ɛ |

ߍ |

met |

sɛ̀nɛ́ |

‘farming’ |

|

i |

ߌ |

happy |

fili |

‘throw’ |

|

u |

ߎ |

goose |

dùgú |

‘earth’ |

|

o |

ߏ |

*like beau in French |

bǒ |

‘excrement’ |

|

ɔ |

ߐ |

bought |

bɔ̀gɔ́ |

‘mud, clay’ |

Syllabic Nasal

|

Syllabic Nasal |

||||

|

Latin |

N’ko |

English approximation |

Example |

Gloss |

|

n |

ߒ |

*Syllabic nasal |

ń |

‘I’ |

Length

In Bambara, all vowels can be contrastively lengthened. For non-native speakers, it is often quite difficult to perceive the difference, but it often serves to distinguish two words that would otherwise be identical. In writing, this marked by simply doubling the vowel:

|

Letter |

Bambara Example |

Translation |

|

a |

baara |

work |

|

e |

feere |

sell |

|

ɛ |

bɛɛ |

all |

|

i |

miiri |

think |

|

u |

duuru |

five |

|

o |

foori |

pull back suddenly |

|

ɔ |

wɔɔrɔ |

six |

Nasalization

In Bambara, nasalization--where the final sound of the vowels passes through the nose--can be applied to all vowels. It is contrastive in the sense that it allows one to distinguish certain words from one another. In writing it is represented by an <n> that follows the vowel that is nasalized. English does not have nasalization, but French provides a few examples. For the other vowels, one must simply listen and try to copy the pronunciation of others:

|

Bambara Sound |

French Approximation |

Bambara Example |

Phonemic Transcription |

English Translation |

|

ɔn |

bon |

/bɔ̃/ |

||

|

ɛn |

bain |

/bɛ̃/ |

||

|

an |

dans |

/dã/ |

||

|

on |

don |

day |

||

|

in |

bin |

grass |

||

|

en |

ben |

fall |

||

|

un |

sun |

fasting |

Pre-nasalization

In Bambara, certain words and syllables can be pre-nasalized, which means that air lightly passes through the nose before the pronunciation of a consonant. In writing this is marked by a letter <n> that appears before the consonant in question:

|

Example |

Translation |

|

nsiirin |

tale; story |

|

nsɔn |

thief |

Keep in mind that this prenasalization does not mean an added syllable; it is more or less just a light addition to the consonant.

Contraction/Assimilation

When writing and speaking Bambara, one often encounters what is colloquially known as “contractions”. This refers to instances where two words appear to combine when the sound of one word is replaced by the sound of the following word. In Bambara, like in English, this is marked by an apostrophe. It occurs when a word ending in a vowel is followed by another that begins with vowel:

A ye à fɔ —> A y’à fɔ.

‘He said it’

Strictly speaking, linguists refer to this as “assimilation” because in reality the vowel does not contract; instead it takes the form of the following vowel. For the purposes of writing however, it is conventional to simply mark it down as if it were a contraction.

Tone

If you aren't familiar with the tonal system of Manding, feel free to consult the dictionary as if it had no diacritics (the so-called "accents" that appear above the letters). To learn more about the system used to mark tone in this dictionary, read on.

Manding is a tonal language. When humans speak, we manipulate our vocal flaps (or “cords”) in such a way that passing air vibrates as a means to produce sound. The speed of the vibrations determines in part the frequency or pitch of our speech. Faster vibrations means higher pitch and slower vibrations means lower pitch. When a language uses the pitch of our voice to encode linguistic information then it is a tonal language.

In Bambara, tone serves two functions. First, it is lexical in the sense that it serves to distinguish words that would otherwise be identical:

|

Bambara Example |

Translation |

|

bá |

‘river’ |

|

bà |

‘goat’ |

Next, tone plays a role in Bambara grammar:

|

Bambara Example |

Translation |

|

Mùsó ̀ tɛ́ yàn |

‘The woman isn’t here.’ |

|

Mùsò tɛ́ yàn |

‘There’s no woman here.’ |

Take note of the fact that the sentences are identical except for the diacritics placed above the letters. Nonetheless, their definitions are clearly distinct. This is an example of the role of tone in Bambara’s grammatical system of definite/indefinite.

Despite the fact that Manding is without a doubt a tonal language, no West African countries have adopted a Latin-based orthography that includes a system for marking tone. This means that you can both freely consult consult and write the words in this dictionary without paying attention to or writing down the tones as we have marked them.

For the purposes of speaking and being correctly understood though, any serious student of the language must take tone into consideration. As such, we decided to mark tone throughout the dictionary using a system adapted from that of Charles Baileul, a Catholic missionary turned lexicographer who produced the most significant piece of Manding lexicography of the 20th century.

Underlyingly, Manding generally has two tones: high or low. In this dictionary, they are marked on the vowels as follows:

- Low tone syllables are marked by a grave diacritic (dùn ‘deep’)

- High tone syllables are represented by an absence of a diacritic (ba ‘river’)

- A grave diacritic on the first letter of a lengthened vowel applies to the whole segment (fàamu = [fààmu])

- In cases where a long vowel is a low-high sequence, each vowel is marked (dàá ‘jar’)

- Modulated low-high tones (that most typically manifest on monosyllabic nouns in citation or in their definite form) are represented by a caron or “hache” diacritic (bǎ ‘goat’)

- The tonal article is noted by an apostrophe-like character that is known as a “Combining grave accent” < ̀> (e.g., Lú ̀ ká bòn ‘The courtyard is big’). For convenience’s sake, and following the convention of Bailleul, when writing nouns in citation form, we omit the tonal article (e.g., lú ‘courtyard’).

Abbreviations

|

adj |

adjective |

|

adv |

adverb |

|

adv exp |

expressive adverb |

|

adv-p |

adverbial prefix |

|

Ar. |

Arabic |

|

det |

determiner |

|

Fr. |

French |

|

interj |

interjection |

|

n |

noun |

|

num |

numeral |

|

part |

particle |

|

ppc |

compound post-position |

|

ppl |

lexical post-position |

|

pref |

prefix |

|

pron |

pronoun |

|

suff |

suffix |

|

vi |

intransitive verb |

|

vq |

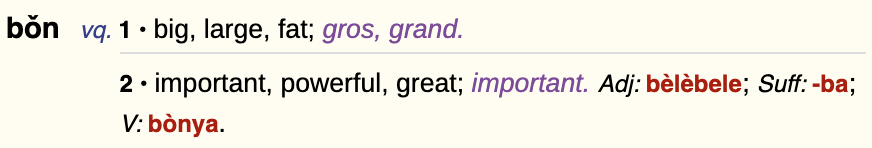

qualitative verb |

|

vr |

reflexive verb |

|

vt |

transitive verb |